Recipe Links:

Doro Wat – Ethiopian Chicken Stew

(Note: adjust berbere spice as needed to lower/increase the dish’s spiciness)

(Also Note: I’m pretty sure this isn’t the recipe I originally used, but that URL has been lost to the ravages of time and a tendency for procrastination)

Soundtrack:

In this day and age true culinary surprises are hard to find; it’s tough to be truly caught off guard by a meal when a world compendium of foodstuffs is sitting in your pants pocket. Almost every meal has some amount of forethought involved nowadays, whether intentional or not. God forbid you want to eat something new, in which case most of us have acquired a natural, though perhaps needless, inclination to thoroughly research the available options in order to try and push back against the tsunami of food you’re presented with by modern technology. After all, with that kind of knowledge so readily available there’s no excuse for being unprepared or uncertain about what comes next. Or if your anxious indecision has reached the point of derangement like myself, every little choice on an eating expedition becomes a roadblock of careful considerations, yearning to satisfy an eternally unfulfilled addiction to certainty. Whether that hankering has always been there or is a byproduct of today’s modern conveniences seems like a chicken or egg scenario. But it’s all in the service of preparing a perfect gastronomic plan of attack. Which is probably why the first Ethiopian food I ate stirred my soul so much: the complete and absolute lack of awareness on my part going into the meal.

I was twenty-five years old when I ate Ethiopian for the first time; I’ve been unabashedly in love ever since. Desperately yearning for something new instead of our usual meager options one weekend, my family stumbled across an Ethiopian restaurant in our unassuming corner of Michigan by happenstance and have been eating there ever since. I fear saying this out loud risks invoking the wrath of the restaurant gods but despite being every inch a hole-in-the-wall by all appearances, seemingly unknown to most and beloved by few, this place has been open for over 25 years now. More than just impressive, that is phenomenal. Practically centuries in restaurant years (think dog years but doubled, maybe even tripled). Especially for such a, shall we say, narrow culinary scene. The idea of opening an Ethiopian restaurant in Michigan in the mid 90s sounds mostly insane with a dash of bravery. While the restaurant does sit right next to a Big Ten university campus, or maybe more accurately because of that, the usual fare in town has been focused on the fast, the cheap, and the greasy. As a result most of the cuisines in town are ones that can mesh easily with that food philosophy: Mexican, Chinese, and American joints galore. With a smattering of Thai, Pho, and sushi restaurants sprinkled in for just a little variety. Not to say that you can’t have a life-changing experience over a platter of crinkle cut french fries, for better or worse. But few morsels have changed the way I think and feel about food like that first grand platter of Ethiopian did when it was dropped off in front of us.

You can never go wrong with serving someone’s meal on a big platter. I don’t care what food is on the plate, a part of you me always feel like I’m receiving some kind of extravagant kingly feast. Out comes our meal, on said platter, placed gingerly on top of a large brightly patterned woven basket called a mesob. And there it is, a feast of colors and textures piled high right in front of our drooling faces.

The platter was (and typically will be) an assortment of wat, or thick stews, with each one focusing on a different ingredient. Meats, vegetables, and legumes, all with an assortment of spices and sauces ranging from light to heavy to extremely spicy. The aroma of those fresh spices flew straight into our noseholes, everyone’s signal to dive right in like a bunch of hyenas. But there wasn’t a fork or knife to be seen, and certainly no hidden utensil pockets on this mesob. Thankfully we took our cues from the other patrons without looking like a bunch of amateurs. Those cylindrical spirals you see strategically placed around the platter is injera, a flatbread made from teff. Spongy and crepe-like, that’s your utensil! Rip off a piece, grab as much food as you can sandwich into the injera with your hand, and enjoy.

I think the reason I love Ethiopian food so much is a combination of the diversity in ingredients and also the nature of eating. It’s easy to throw together a really unique array of foods in one meal, whether you want meats or vegetables or legumes or everything that’s offered. You can spend the entire meal sampling each variety one by one or mixing them together in different combinations to find what best tickles your fancy. Plus eating with injera is a lot more tactile and just so damn fun.

The communal nature of Ethipian feels so much more intimate than any other cuisine I’ve eaten as well. Sitting close together with friends or family, all of us hunched over one big plate. No dividers or individual placemats or anything to imply even a whiff of separation. Politely grabbing at different sections of food while trying to avoid any crossing of arms. We are all in this meal together. Similar to the feelings you receive from hot pot meals or any cuisine with a more collaborative system of eating, but it’s hard to feel as close when you’re separated by a giant grill or pile of hot coals.

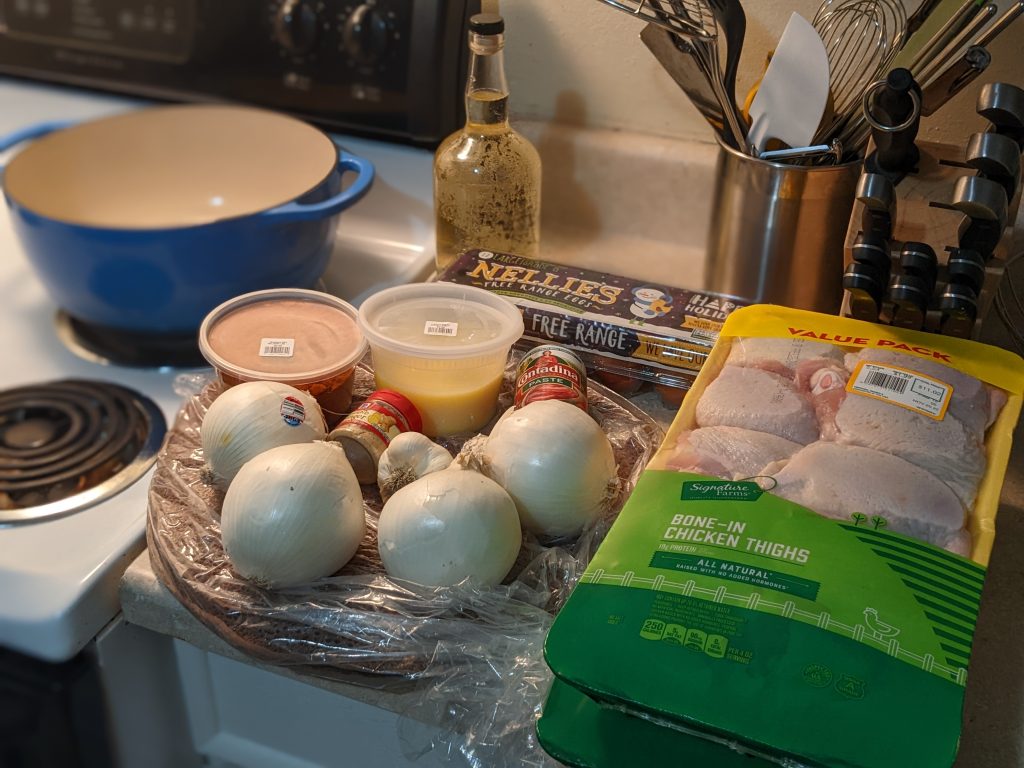

Now I’m only one man, so cooking an entire platter of Ethiopian food myself in one go would have been a tad excessive in addition to a whole thing. I decided to keep things simple and only make Doro Wat, one component of that delectable platter I was just gushing over. It’s a spiced chicken stew, and I would hazard to guess probably the most internationally-known recipe in Ethiopian cuisine. But I needed a few key ingredients that would also make or break the whole meal and I had neither the time, inclination, or skillset to prepare from scratch. In other words, best left to the experts.

Luckily enough for this hack, Denver happens to be home to a sizable Ethiopian population. I had my pick from at least a dozen specialty African markets that sold the ingredients I needed: injera, biter kibbeh, and berbere spice. The injera came as a nice grey shortstack wrapped in a plastic bag, another reminder that I need to eat more pancakes. The bread can vary in color depending on the type of teff used, mine was a fairly boring grey but the taste was spot-on. Biter kibbeh is a seasoned clarified butter, similar to ghee (not that I know anything about that either) except simmered with spices, used in many Ethiopian dishes. And last but not least, Berbere is an Ethiopian spice blend, a mixture of chili peppers and a few other fairly common spices, that gives the stew its flavor and kick. But after this recipe the blend has gained a permanent spot in the spice cabinet: I just throw it on everything that needs a little more flavor. And believe me, this mix kicks like a donkey. The recipe I used called for 2/3 cup, at that amount I was only able to eat maybe half a bowl at a time before the heat overwhelmed me. Granted I am a pale-faced boy from the hinterlands of Connecticut so my spice tolerance, while certainly above average, certainly isn’t remarkable. But just tread carefully with the stuff.

Once you have those ingredients ready the recipe itself is a fairly simple one: simmer a whole lot of diced onions (apparently a big part of what separates wat from other stews is that you start with slow cooking onions then sautéing them with your aromatics), add your spice/biter kibbeh/tomato paste/etc., sauté, then throw in your chicken followed shortly after by your water, and cook it all up.

Honestly the hardest part is peeling all of those damn hardboiled eggs for. My only fatal flaw was that the stew ended up more viscous than I would have preferred, making it less easily consumed via injera. Next time I will probably forgo the recommended water volume and add a lot less. But the taste still came out fairly well as far as I’m concerned.

Stew all set, I found myself left with an entire tray of unused chicken and a whole bucket of spices. I quickly whipped up a batch of berbere-spiced roasted chicken in my oven, just throw on the spices and go to town. Nothing too fancy, but boy oh boy those spices take care of everything.

As for the berbere spice, I decided to try out a fusion of Ethiopian and pure white trash. Around this time I had been talking to a friend who reminded me of the existence of Annie’s mac & cheese, a staple of my childhood, and in a moment of weakness I had grabbed a box or two on a groceries run that week. Thank God I didn’t grab a package of hot dogs too and really go to town. But my god, it was worth it for the lip-smacking, ASMR-inducing sound stirred cheese alone. I mean just listen:

If anyone wants to put that sound on a loop and throw it on Youtube please make sure to share the ad revenue. But throw on a good portion berbere spice, add in a few florets of steamed broccoli to pretend you’re being remotely healthy, stir some more, and voila! A refined masterpiece of elevated garbage food emerges. And who says globalism is a bad thing?

This might be surprising to hear, but growing up in what I personally consider one of the WASP capitals of the world there wasn’t exactly an abundance of cultural exchange going on. When it came to eating out or ordering in we kept mostly to our staples: American, Mexican, Italian, Chinese, Japanese (read: sushi, maybe hibachi for a birthday), and that was that. A quick Google search reveals that the nearest Ethiopian restaurant to my hometown is a 30 minute drive away, and who knows if it was open way back when in the early aughts. Not that I ever would have even thought to drive so far for a food I had never heard of. I mean why drive all that way when Duchess was right down the road? (That’s a fast food deep cut for you CT folks). But after a few years of family food trips and a few more years of driving around in search of late night diner food or late morning hangover BEC sandwiches in the green Oldsmobile you got (read: took away so she couldn’t drive) from your grandmother, high school ends. The baby boy heads off to university, determined to broaden his cultural horizons and nourish his knowledge. So naturally he goes to the most diverse and far-flung city he can think of: Boston, Massachusetts. And from there comes a few more years of hopping around from Boston to New York City to Michigan, with plenty of food exploration but apparently a gap when it came to one West African country.

Cooking this recipe and reflecting on my first exposure to Ethiopian cuisine had me wondering about how we’re exposed to different cuisines and when. Is twenty-five too old or too young for me to have encountered Ethiopian food for the first time? The question feels like something from one of the probably-hundreds-at-this-point of Law & Order spinoffs arguing whether a perpetrator of the latest especially heinous crime should be tried as an adult or not. Ice-T by my side, spouting some insane nonsense, while Dick Wolf rides off into the sunset with another truck full of money (Another question for another time; How old were you when your realized Elliott Stabler was really the bad guy, and that one Internal Affairs agent we all hated was the real hero?). In a conversation with another friend it came up that I’ve never eaten Filipino food before, and I’m sure there’s a few dozen other cuisines I could have that same exact conversation about. But the point remains, when do most people first encounter lesser-known or more-distant foods, if ever?

The bad news is that I couldn’t find a lick of research that really looked into this sort of thing besides some sample data from a research company some hokey puff piece surveying at what age people were when they had their “food awakening,” whatever the hell that means. Understandably, most research I found looking at access to specialty markets or Asian/African groceries focused on food insecurity, societal diet changes, and community access to groceries or the cultural assimilation of international cuisines (Even found an article from the alma mater!). I’m sure a marketing research company or international body looking at at food somewhere has statistics on this, likely buried within a report looking at what people buy to eat and why. But I would love to see the statistics on exposures to different cuisines, preferably filterable by geographic location, ethnicity, income level, and a whole bunch of other factors I have no doubt influence the answers. But for now I guess I’ll just have to speculate and stick to anecdotal evidence.

I suppose the point I’m trying to make here is that we all have our own bubbles we’re stuck inside. Some a result of our upbringings, others a product of our lot in life, and more still created by our own actions. What can be done about this? Well it depends. These bubbles aren’t necessarily a bad thing; these bubbles are how we build our communities, find common ground, and create strong bonds with other people. I think the problems emerge when you are unable (or maybe refuse) to recognize and acknowledge their existence along with the need to tread outside them occasionally for a different perspective. I will never fault anyone for never trying Doro Wat before the same way I would hope no one can be angered by my own lack of exposure to Uruguayan or Australian or Djiboutian (definitely not a real word, just wanted an excuse to say that) food. But I will fault them for not at least trying a bite.

Notes for Next Time:

- Thicker stock

- Try out cooking the other wat varieties, in anticipation of the eventual Ethiopian feast with friends

- Broaden my food horizons more

- Go eat some Filipino food